|

| US embassy/Ina Navazelskis |

A collection of Navazelskis' reports have recently been published by "Versus Aureus" in a book "Fragments and Fissures: Reports from Vilnius 1990—1991." The following is Ina's, who later married one of the Act of Independence signatories Virginijus Pikturna, essay from 15 March, 1990, on Lithuania's declaration of independence.

***

Sunday, March 11, was overcast, wet. A light drizzle fell, sometimes escalating into rain, sometimes tapering off into mist. It did not seem the kind of day that anything much should happen certainly not anything as momentous as declaring a nation’s independence.

The streets of Vilnius were empty. Only some 300-500 people, braving the clammy weather, waited outside the Supreme Soviet ( aka Parliament, aka the Supreme Council) in the heart of the Lithuanian capital. A few had been there from as early as 8 A.M. (The morning session only began at 10 A.M.) As evening fell, some people held lighted candles, shielding the flames from the rain. Others pressed flowers into the arms of their heroes -- the newly elected parliamentarians -- who occasionally appeared in the front courtyard. The crowd sang, cried, clapped. Some people shouted "Vytautas!" (calling for Sajudis leader Vytautas Landsbergis); others simply said "Ačiu!" (Thank you!)

It was not anywhere near the mass turnouts of hundreds of thousands of people, so common over the past few years. But to participate in this, the parliamentary manifestation of the “reestablishment of the Lithuanian state" it was not necessary to be present in body -- spirit was enough. So most people in Lithuania sat at home, glued to their television sets. Independence was thus witnessed in private circles of family and friends.

That did not make it any less THE national public experience. When at 10:44 P.M. Vytautas Landsbergis, the newly elected President of the Parliament, declared that "The act has been passed. I congratulate the Supreme Council: I congratulate Lithuania" one knew, without actually seeing it, that champagne corks popped and tears flowed across the country. It was all a bit mind-boggling. Less than two years ago, independence had still been the subversive idea, the forbidden word, the unreachable goal. (Indeed, only a few brave souls nervously floated the notion of “sovereignty" for the republic.) Now, all of a sudden, here it was -- in living Technicolor.

|

| Kęstučio Vanago/BFL nuotr./January 1991 people had to defend the recntly-declared independence from Soviet tanks. |

Television had made this a shared public experience; yet, it was also intensely personal. Older people remembered what it had meant to survive fifty years without independence. Its loss in 1940 -- sanctioned by two great dictators, one a neighbor to the east (Stalin), the other to the west (Hitler) -- had ushered in an era that signaled more than foreign occupation, more than a new ideological order. It was an era that had mercilessly destroyed people; thousands physically, many more spiritually. From the dissidents who only recently sat in Soviet jails for having dared to openly demand independence -- a handful, including Balys Gajauskas (a 37 year veteran of Soviet prisons) were now newly-elected parliamentarians -- to those Communist Party apparatchiks who secretly gnashed their teeth each humiliating time Moscow reminded them who was boss, to the collective farm workers who bitterly remembered that once, before deportations (which for thousands meant death), they had owned their own land -- tragic individual destinies spanned several generations.

But how did a nation, so clearly defeated, manage to resurrect itself from "the dust heap of history"? (to borrow a phrase that Leon Trotsky once used to consign Russian anarchists)

Although strong-armed by Josef Stalin and Adolf Hitler, and forcibly annexed to the Soviet Union in 1940, Lithuania had never been entirely vanquished. At first there had even been armed resistance. As the Red Army began its march on Berlin in late 1944, a bloody guerilla war broke out in Lithuania. It dragged on until 1953. Although there are no concrete statistics (yet), it is estimated that the cost was at least 50,000 lives -- this in a country of less than 3 million people. And it all happened on the heels of World War II, when Lithuania was several times the battleground between Nazi and Soviet forces.

In the post-war Europe that emerged, such resistance was of course doomed. Outwardly it looked as if most people had finally, however unwillingly, accepted defeat and with it, the new status quo. But over the years the need to delineate an identity separate from the violently imposed Soviet one -- inwardly Lithuanians always groaned whenever foreigners mistook them for Russians -- became a form of resistance that had a power all its own.

That resentment, that stubbornness, that unwillingness to reshape themselves into prescribed versions of "homo sovieticus" laid the necessary psychological foundations to resurrect the goal of political independence. Although for decades submerged, such resistance found expression in ways both subtle and creative. It very rarely was political -- at least not in the direct sense. It could not afford to be.

Setting the Stage

For 61 year old architect Algirdas Nasvytis, for example, resistance meant following his own inner vision professionally. For him, March 11 marked the ultimate reward after 20 years of discreet but determined effort. As the chief architect of the Lithuanian Parliament, years ago Algirdas Nasvytis, together with his twin brother, Vytautas, consciously, quietly, and quite literally set about building the stage for Lithuanian independence.

Their work began in 1970, when the brothers won a republic-wide competition to design a new government complex. Given their bourgeois pedigree, the award of this contract was unusual. Neither brother was a member of the Communist Party. And their connection, through a cousin’s marriage, to the family of the ultimate persona non grata -- Antanas Smetona, who was the former president of Lithuania from 1926-1940 -- was even more incriminating. Their ideological unsuitability was overlooked, but the step from blueprint to building nevertheless took over ten years. (This was, after all, still the Soviet Union.) Today, the entire modern government complex is located at the end of Vilnius’ mile-long central boulevard, Gediminas Prospect -- known until last year as Lenin Prospect. Parliament itself is a modern square four story white building with large rectangular orange tinted glass windows. In front, three sides extend out to frame an airy open courtyard. In back, parliament is buttressed by the Ministry of Finance and the Trade Union Council buildings. Flanked on one side by the Neris River, on the other by the Mažvydas State Library, (an imposing structure reminiscent of a Greek temple), Parliament is separated from them by a vast concrete plaza -- ideal space for rallies and demonstrations.

Inside the main entrance, immediately to the right of huge brass double doors, a desk with phones in various colors is manned by militia men, who check everyone’s ID cards. The airy foyer -- the ceiling is two and a half stories high -- is lined on both sides by plush brown velvet armchairs and modular sofa sections. (occupied, during the past month, mostly by weary foreign TV crews.) A staircase on the left leads up to a hastily set up Pressroom (second floor) and President’s office (third floor) A staircase on the right leads up to offices of Presidium members and a large conference room (also third floor). Two other staircases, recessed at the back, lead to the central chamber of Parliament itself. The center of the main lobby, a sunken enclave, is also lined with sofas ideal for discreet and comfortable lobbying.

The total effect is functional, spacious, business-like. While there are none of the signs of wealth, such as gleaming brass fixtures or smooth imported marble, so often found in modern buildings in Western countries, there is also an absence of the shoddiness so common in structures throughout Eastern Europe. (All the materials used to build and furnish Parliament, save for granite floors from the Ukraine, and the orange-tinted as well as stained glass windows from East Germany, were produced in Lithuania.)

As he sat inside the central chamber in Parliament recently, architect Algirdas Nasvytis fit in well with the environment he created. He wore a light yellow shirt and sported a dark mustard colored suede jacket. He sat in a flap seat upholstered in a deep golden fabric, and scanned walls that were a neutral beige. A diminutive man with thinning wavy silver hair, Nasvytis clearly favored the same color schemes -- various hues of beige and gold -- in his personal attire as well as his interior design.

He definitely did not look like someone who rebelled against the established order. But Nasvytis is a perfect example of that subtle resistance to Sovietization which at first glance is usually not recognizable. Some Lithuanians themselves mistook it for something else entirely. The comments Nasvytis heard when Parliament first opened its doors in late 1983 testify as much. Why, he was then asked, had he designed such a nice building for those rotten Communists? Because, he answered, “someday a real Parliament will appear,” and then “the building will be ours.”

Nasvytis had purposely designed Parliament to easily accommodate such a monumental change. If you look closely, he explained, you cannot find any permanently built-in symbols heralding the "Soviet Socialist" part of the Lithuanian Republic. Neither the two large bronze reliefs on either side of the entrance to the building -- which show human figures moving in the same direction -- nor the stained glass windows in the lobby display the well-known Soviet hammer and sickle. And, added Nasvytis, those Soviet symbols that are in place -- such as two large bronze Soviet Lithuanian crests -- one above the main entrance and the other in the central chamber -- can easily be removed. Nasvytis recalled that when the building was first completed, the President of the Supreme Soviet at the time noticed this peculiar absence as well, but did nothing about it.

The Power of Symbols

Maybe he should have. On March 11, those Soviet symbols disappeared just as easily as Nasvytis predicted that they would. At about 7 P.M., as foreign television cameras rolled, theater director Jonas Jurašas, one of the honored guests at the day’s ceremonies, directed perhaps one of the more politically satisfying acts of his career. (Jurašas had left Lithuania in 1974 after publicly resisting censorship of one of his plays; he went on to direct productions both on-and off Broadway. Now he was back for an extended visit, directing a play at the repertory company from which he had been kicked out almost 20 years earlier.) As a few young men climbed up to tear down the bronze Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic crest above the front entrance to Parliament, Jurašas shouted out directions from below. Later, a batik tapestry featuring a medieval knight on a horse, (a traditional Lithuanian symbol called a Vytis), was hung in the empty space.

It was rumored that this entire spectacle was not so much a spontaneous act as the inspiration of foreign television crews, who of course had nothing against capturing a split-second visual that said it all... If so, their suggestions were more than willingly accepted. But there really was no need to suggest anything. The removal of Soviet symbols was written into the ceremonies. Later in the evening in Parliament’s central chamber, as the tri-color yellow, green and red Lithuanian national flag covered the second Soviet Lithuanian crest behind the rostrum, people stood and clapped.

Thus the hammer and sickle disappeared from the citadel of Lithuanian government; and the much-revered symbols from a longed-for past were restored. The national flag, the Vytis, the Posts of Gediminas -- all these traditional Lithuanian symbols had been adopted by the independent government during the inter-war years. They therefore represented not only cultural and national traditions, but the one brief period in modern Lithuanian history when she was free from foreign domination, and which, quite understandably, the Soviet Union sought to stamp out from living memory. It is not surprising that only two years ago the public display of reminders from that time -- even for a furtive few minutes -- was enough to earn one a hefty jail sentence. That, however, only increased their value (Last year, when the novelty of displaying national symbols was still new, I asked one man why there was so much emotion attached to what were, after all, merely representations of things. He answered by relating an incident from his own childhood. In 1940, soon after the Soviet occupation, he saw a Red Army officer kick the corpse of a Lithuanian soldier, who wore the Posts of Gediminas on his uniform. The man was then ten years old. That was the last time, he said, that he had seen this medieval Lithuanian crest in public.)

In summer, 1988, the appearance of these long-forbidden symbols had signaled the beginning of the opposition movement, Sajudis. Meetings, demonstrations, grass-roots initiatives all followed. They were all important gestures, awakening a common spirit amongst Lithuanians that people had thought had long ago been extinguished. The culmination, the most important gesture of them all, was the declaration of independence. In keeping with all the events leading up to it – all of which were extraordinarily indicative of the turbulence in society -- it too, was entirely symbolic.

For the independence declaration to have been more than that, other signs -- less evocative, but more substantial, such as one’s own tanks and one’s own currency -- would have had to have been in place. But the soldiers in the streets -- most of whom spoke no Lithuanian -- still wore Soviet uniforms, and the currency one used to buy bread was still the Soviet ruble. At certain moments it seemed that the new Lithuanian leadership believed if the sacred word "independence" was repeated often enough, it might actually become reality. (It reminded me of a phrase Khrushchev once uttered, “You want it so badly, but Mama says no.")

Symbols Have Limits

The enthusiasm for independence was of course real enough; the tears shed in front of television sets around the country were real enough. After all, in the February 24th elections to the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet, the Sajudis candidates had campaigned on the platform that their fundamental purpose was to reestablish the independent Lithuanian state. They were simply following through on that promise. And although sudden, in Lithuania the declaration wasn’t really a surprise. Most political activists here had predicted that it would be declared sometime this year. But as recently as a month ago, few would have said it would happen so soon.

In practical terms, everyone recognized just how unprepared Lithuania is. She has no military force to back up the move, no reserves of food (although food products are a substantial part of the republic’s national product) no raw materials, no gold.

The declaration was thus an act of will rather than of reason. Of course, there were various rationalizations offered for why it made cold sound sense to declare independence NOW. The most compelling one was that the Extraordinary Third Session of the Soviet Congress of People’s Deputies, scheduled to begin in Moscow on March 12, would pass amendments to the Soviet Constitution making it almost impossible to leave the Union. In addition, it was expected that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev would be named to the newly created post of President, and would have the means to consolidate almost dictatorial powers. Neither of these events boded well for Lithuanian interests; it was thought that declaring independence before all this took place would give Lithuania greater leverage juridically. (A joke making the rounds in Vilnius these past few days: Q: Why is Gorbachev in such a hurry to become President of the Soviet Union? A: So that when he meets with Vytautas Landsbergis, he will feel like an equal.")

But was that all that was necessary to push Lithuania over the brink? At one point before the February 24th elections, Vytautas Landsbergis hinted at another reason: Lithuanians were simply fed up. "Fifty years is enough," he said, adding that if it was not too soon for the Berlin Wall to come down, not too soon to talk about East Germany reuniting with West Germany, then it was not too soon to talk about Lithuania’s independence. "We are ready,” Landsbergis said -- even if the rest of the world is not.

So, during the two weeks preceding March 11th, the momentum in Lithuania suddenly sped up. The sentiment emerged: Either now or never. It became nothing less than political suicide to urge restraint. To be against independence now was equated with being against independence, period.

Throughout February, almost all Lithuanians I spoke with were unhesitating in their support of independence. Typical was a 70 year-old man, a former airplane pilot. I stopped him on a street in Vilnius’ Old Town and asked him what he thought about Lithuania declaring independence. His face was lined with wrinkles, he had piercing blue eyes, and he carried hefty shopping bags. His answer came fast and unequivocal. “I would live on bread and water,” he said, “just give me freedom.” And he pointed to his Russian wife, who stood off to the side, smiling. "She thinks so, too,” he added.

He was echoed by a 60 year-old physician, Petras Tulevičius. Interviewed on February 24th at his polling place, a local school in Vilnius’ Antakalnis district, Tulevičius said that he had voted for the Sajudis candidate. Why? "Sajudis is the only force in which I can believe,”| he said “The most important thing for us is to go out from the Soviet Union”. And, he recalled, “I was ten years old when Lithuania lost independence. I remember the day the. Russians came with tanks. I could not understand everything, but I could understand that something was very bad.”

After half a century, during which time Lithuanians were erased from international consciousness -- there were also concentrated efforts to erase them from the earth -- was argument that they were now being impatient entirely fair?

The Elections to the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet

Still, public support and psychological readiness alone are not enough to explain the rush. There was also another reason, one common to elections the world over: The winners wanted to secure their power. A minority of idealistic, disillusioned Lithuanians -- in addition to the naturally disgruntled losers -- said, “This declaration is merely a means for some Sajudis individuals to be written into the history books.” It was of course much more than that. But it was that too.

For Sajudis, which won such a landslide, still felt threatened by the independent Lithuanian Communist Party (LCP). In forcing the issue now -- the LCP preferred a more gradual, less drastic approach to independence -- some Sajudis activists hoped the LCP would balk. It could then be "unmasked", revealing to the entire nation that it really was still the same old morally bankrupt Party pledged to do Moscow’s bidding rather than Lithuania’s.

But why was Sajudis so alarmed? After all, the LCP had been trounced in the elections. In the entire 72-year history of the Soviet Union, for the first time non-Communists emerged as victors. Indeed, in the first round of elections, 59 of the newly-elected deputies were non-Communists. Forty-eight belonged to no party at all.

During that first round, Sajudis won a full 80% of the seats. (There were 141 seats in all; 90 were decided on February 24. Of that 90, Sajudis-backed candidates won 72 seats (or 80%); of those 72, only 15 went to LCP candidates who ran under the Sajudis banner. On its own, the LCP won only 12 seats.)

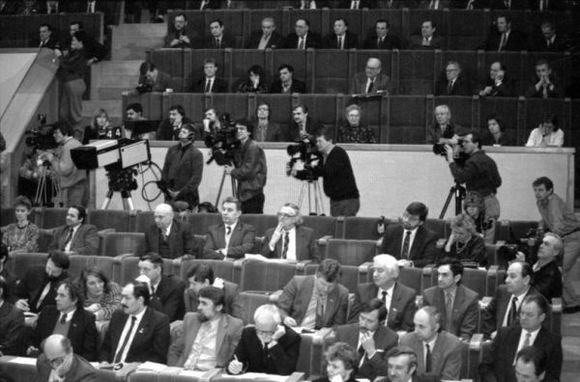

|

| Seimo archyvo/ Algirdo Sabaliausko, Pauliaus Lileikio, Jono Juknevičiaus nuotr./Members of the Supreme Council |

By the time the first session of the new Parliament convened on Saturday, March 10, 133 of the 141 seats had been decided. Ninety-eight went to Sajudis-backed candidates (of which 22 were LCP members.) Twenty-four went to LCP candidates not hacked by Sajudis. The LCP, therefore, had a total of 46 seats in Parliament. Six seats went to the rump Communist Party (LCP/CPSU platform) still loyal to Moscow. The rest were held by those few deputies supported neither by the LCP or Sajudis.

With only 22 LCP deputies not backed by Sajudis elected to the Parliament, it was perfectly clear that this was a resounding vote against the party. As Algimantas Čekuolis -- newspaper editor, executive council member of Sajudis, AND member of the LCP -- succinctly put it, “Just to be in the role of 50 years of collaboration is a sin” which Lithuania’s voters would not easily forgive.

Nevertheless, the LCP, discredited, its days as a ruling force numbered, had staged a certain comeback. Under the direction of First Secretary Algirdas Brazauskas, the LCP’s dramatic split from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in December, 1989, gave the Party a fighting chance in the February elections. Support was of course very modest -- one pre-election poll showed only 12% of the respondents saying that they would vote for it. But for the first time in half a century, that support was genuine. And in late December, for a brief ephemeral moment, the LCP even managed to steal the limelight from Sajudis. Just after the LCP officially broke away from Moscow, people poured into the streets the day after Christmas to cheer Brazauskas. The Party’s ranks were thinning out; party cards were being returned daily. Yet at that moment, a few hardy individualists, who never would have imagined it a year ago, actually joined the Party.

But the LCP did more than just steal some of Sajudis’ thunder. It co-opted the core of its political platform as well. In a dramatic break with past policy, the LCP now adopted political independence -- not autonomy, not sovereignty -- as the basic cornerstone of its program. During elections the previous year (March, 1989) to the all-Union Council of People’s Deputies, the LCP’s policy had been quite different. "We cannot cross that line" from sovereignty to independence, Brazauskas had said to me in an interview then. (The LCP paid dearly for that position. Of the 42 seats up for election in Lithuania to the Council of People’s Deputies, 36 went to Sajudis-backed candidates.)

But the February 24th, 1990 elections to the Lithuanian Supreme Soviet were an entirely different matter. At least officially, there was no longer any significant distinction between the goals of both major political forces in Lithuania, Sajudis and the LCP. Unlike the year before, voters now did not have clearly drawn sides from which to choose. To further confuse matters, some of the candidates that Sajudis backed, as an umbrella reform movement, were also members of the LCP. A few Sajudis leaders -- such as Romualdas Ozolas and Kazimiera Prunskiene, both also LCP members -- had also joined the Party’s Central Committee in the past year. All the candidates now wrapped themselves in the newly resurrected symbols. All talked alike. How were voters to know the differences between one candidate and another?

Pre-election pundits declared that voters would find their way out of the muddle by voting for individuals, whose backgrounds and work they were familiar with, rather than party platforms. In a confusing election, it was explained, this was the only way that they would be able to distinguish who was who. A pre-election poll in early February reported that 36% of the respondents surveyed said they would cast their vote based on a candidate’s "personality". And in February, 1990, the most popular politician in Lithuania was a Communist, Algirdas Brazauskas. He outranked the most prominent Sajudis leaders Kazimiera Prunskiene, Romualdas Ozolas, and Vytautas Landsbergis. It gave Sajudis the jitters.

A year ago, things had been very different. Then, during elections to the all-Union Council of People’s Deputies, Sajudis had actually saved Brazauskas’ political skin. In March, 1989, the future direction of the Lithuanian Communist Party was still unclear. Fierce internal battles erupted between reformers such as Brazauskas and the hard-line apparatchiks who longed for the good old days. Sajudis was faced with a dilemma. Its candidate, a nonula young philosopher named Arvydas Juozaitis, was pitted against Brazauskas in one small district of Vilnius The chances were very high that Juozaitis would defeat Brazauskas, and that would probably result in the latter being removed as First Secretary of the republic. Sajudis decided this was too great a risk, and Juozaitis stepped aside. It was not a gesture of goodwill -- it was calculated, enlightened self-interest. Sajudis did not want someone worse than Brazauskas -- perceived as spineless but more acceptable than the standard CP apparatchiks -- in that spot.

Brazauskas’ popularity in March 1989 was at a dangerously low point -- he was still feeling the stigma of having failed to follow Estonia’s lead and declare Lithuanian sovereignty in November 1988. That failure, he admitted in our interview on the eve of the March, 1989 elections, had cost him dearly politically. His position within the LCP had not been strengthened, and whatever support him reform Policies had amongst the population evaporated.

A year later, Brazauskas had learned well from his political mistakes. And such self-interested generosity on Sajudis’ part had vanished. Brazauskas was now perceived the greatest threat to the reform movement’s consolidation of power. In his native district of Kaišiadorvs, Brazauskas had won a whopping 91.7 of the vote; almost a full third more than the 60% than the citizens of the fifth largest city in Lithuania, Panevėžys, awarded their victorious Sajudis candidate, Vytautas Landsbergis.

(Brazauskas’ popularity today is unquestioned. When I saw him debate his Sajudis opponent, a cardiologist named Alfredas Smailys in Kietaviškės village (main means of subsistence; fish-farming) some 60 kilometers to the west of Vilnius, there was no contest. Most of the villagers did not know Smailys’ name, paying no attention to the campaign posters hanging in the village Party headquarters. Brazauskas was the hero of the day; the villagers turned out to see the man who had stood up to Gorbachev. The hallways of the small two story party headquarters were packed. They clapped politely for Smailys, but their cheers and enthusiasm was reserved for Brazauskas. Smailys himself was deferential. Probably realizing he stood no chance of winning, his manner towards Brazauskas was more that of a friendly challenger rather than ideological enemy. As Brazauskas left the meeting-hall, escorted by what seemed to be the entire village, to two cars where aides from Vilnius waited to rush him off to the next campaign stop, Smailys stood at the side, ignored. Humble as Brazauskas’ two-car campaign entourage was, it still outshone what Smailys had to offer. Minutes after the First Secretary drove away, the Sajudis candidate got into a yellow Soviet tin box of a car, and with no-one waving good-by, putt-putted off by himself.)

Thus, Brazauskas, who could not save the Party, nevertheless managed to save himself, and a few other top Party officials. True, none took any chances: all ran in remote districts where they were assured of victory. They were not disappointed. In addition to Brazauskas’ 91. %, second secretary of the Party Vladimir Beriozov won 79.7%, Central Committee Secretary Justas Paleckis won 75.0%, and Central Committee Secretary Kestutis Glaveckas won 60.4%. The Party leaders, still unused to the idea that they would no longer be calling all the shots, were certain that these returns could guarantee them a substantial voice in a new coalition government.

They couldn’t have been more wrong. In the two weeks between the February 24th elections and the March 11 declaration of independence, the victors of the elections virtually ignored the LCP. Sajudis formed a "Sajudis Deputies Club" (SDC), whose members were all the Sajudis-backed winners in the elections. Their task was to draw up the necessary documents for the takeover of power and the declaration of independence. They worked, it seemed, sometimes round the clock.

The Club had little time for the. LCP Before the first week of the new Parliamentary session was over, Vladimir Beriozov complained of a nascent witch-hunt against the Communists, "We were virtually ignored" he accused the Parliament’s new deputies, adding that the first time the LCP was brought in on any debate was during an open meeting at 4 P.M. March 10, the eve of the declaration of independence.. The reply from Sajudis’ Kazimieras Uoka, a former bulldozer operator, came fast and biting. What talk of a witch-hunt can there be, he responded angrily. "When we were only five of us amongst several hundred (in the former Parliamentary plenary session) we did not use such terms."

Uoka was of course right. The LCP might accuse Sajudis of being gloating winners, but they were not exactly gracious losers. Still, Landsbergis met with Brazauskas no more than a handful of times during the two weeks prior to March 11. Both men wanted the post of President of the Supreme Council -- Brazauskas to retain it, Landsbergis to win it. Both men were confident of victory.

One was to be sorely disappointed. In the final days, Brazauskas’ name evoked snickers during discussions in Sajudis Deputies Club meetings. The few Sajudis members who suggested that Brazauskas be retained as president of the Parliament, in the interests of a smoother, less jolting transition to independence, met, at best, with stony silence. The dominant sentiment was that if Brazauskas stayed, there would be no declaration of independence at all.

There was some justification for this, for Brazauskas, visiting Gorbachev in early March, returned to Vilnius urging restraint. Gorbachev had warned him that if Lithuania decided to break away, all further payments for goods from the Union would have to be in hard currency -- currency which of course Lithuania did not have. In addition, border regions in the southeast part of Lithuania as well as the port city of Klaipėda were territories that the Soviet Union hinted at laying claim to. The message was aimed to upset Lithuanians, and it did. Being cast as the bearer of bad news did no great wonders for Brazauskas, either.

March 11 at the Supreme Council

Still, he believed that he had a fighting chance for the post of President of the Parliament. Throughout the week and a half prior to March 11, petitions had been circulated amongst people calling for Brazauskas’ election to the post. Sajudis angrily charged that this was an organized campaign whose purpose was to snatch away victory from those who had justly won it. LCP advocates retorted that it was nothing of the kind -- the petition campaign was a spontaneous, genuine reflection of public opinion. Most likely, it was both.

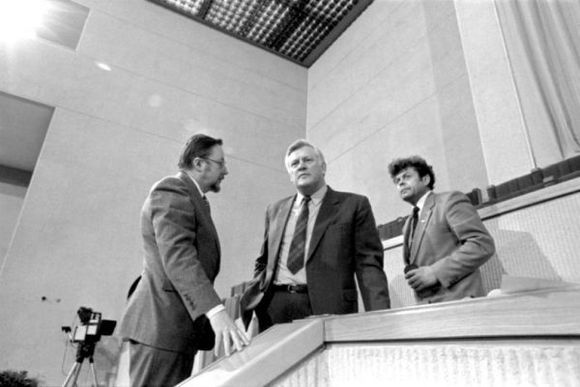

In the early afternoon on March 11, both men addressed the Parliament’s plenary session, Landsbergis following Brazauskas. Both fielded several questions from various deputies -- Brazauskas agitated and embattled, Landsbergis calm and confident. Brazauskas repeated his by now well-known views, “The restoration of independence is our immediate task recognized by all Lithuania,” he said, but also cautioned, that “If we only have political sovereignty, is not enough. We must work very hard to have economic sovereignty”.

But Brazauskas’ moment of glory had passed. March 11th was Vytautas Landsbergis’ day. While the one spoke of caution, the other spoke of vision. “We need to come to our free land and defend our lives and those of our children,” Landsbergis said, and added, "I would like to say one thing, as I feel it. Beyond us, and within us as well, are the expectations of many of the people of Lithuania. An expectation of what will be, and worries about how things will be. It seems to me that this expectation is greater and our determination is greater than fear. Who will best be able to contribute to whether that expectation becomes reality? What your hearts, intuition and experience tell you -- that is the one you should vote for. Your will expresses the will of the people of Lithuania."

At 330 p.m., a vote was taken. There were 38 votes for Brazauskas, 95 votes against. There were 91 votes for Landsbergis, 42 votes against. The deputies all rose, clapping. It had been expected.

Another six and a half hours passed before the second, most crucial vote of the day was taken. In between, there was a letter read aloud from the last Foreign Minister of independent Lithuania, Juozas Urbšys, a speech from the former Russian dissident, Sergei Kovalev, greetings from Czechoslovakia’s Civic Forum. After 10 P.M. now President Landsbergis read the act reinstating the declaration of independence. Voting was by alphabetical roll call, the deputies standing to acknowledge their vote. One hundred twenty-four -- Brazauskas included -- voted for it. Six -- all members o the LCP/CPSU platform -- abstained. Three deputies did not participate. It took about five minutes to read all the names. Five minutes -- plus fifty years -- to reinstate Lithuanian statehood. Five minutes to deal the first blow to what was the Soviet empire.

Many went to bed that night feeling they had witnessed history being made. New players had emerged on the stage that Algirdas Nasvytis had built. How long would they -- and the independence they declared -- survive?

|

| Seimo archyvo/ Algirdo Sabaliausko, Pauliaus Lileikio, Jono Juknevičiaus nuotr./Vytautas Landsbergis, Algirdas Mykolas Brazauskas, Česlovas Stankevičius |